:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-954286708-388d95e8561449f6b78967110eec70ba.jpg)

Have you ever wondered why your hot food eventually becomes cold 😅? In this blog post, we embark on an interesting journey to understand the fundamental principles underlying this phenomenon. While I'll touch on some technical terms, my aim is to make these concepts accessible to everyone by minimizing the use of mathematical equations.

The First Law of Thermodynamics

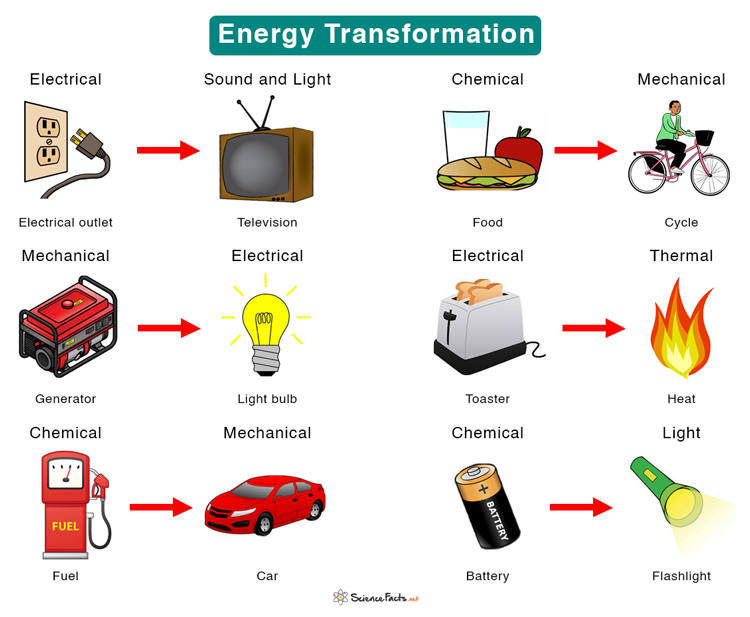

The first law of thermodynamics, also known as the law of conservation of energy, states that energy cannot be created or destroyed in an isolated system . It can only change forms from one type to another or be transferred from one part of the system to another.

A diagram showing various types of energy transformation. Source: ScienceFacts.net

A diagram showing various types of energy transformation. Source: ScienceFacts.netThe First Law of Thermodynamics, while valuable for understanding energy conservation, doesn't address the practical constraints of energy conversions—whether it's physically possible to convert all the energy of a body into useful work.

Problem.

Picture a scenario where a heated object comes into contact with a cooler object, and over time, you notice that the hot object has gotten even hotter while the cold one has become even colder. Does this scenario violate the first law of thermodynamics?

Work

The concept of work is frequently used in the fields of Science and Engineering, but what precisely does it entail? To put it simply, work is determined by multiplying the distance a body travels by the force that acts against its motion. In essence, when moving a body from point A to point B, energy is expended to overcome any opposing forces. If there are no opposing forces, no work is performed.

Work can be calculated by multiplying the magnitude of the force by the distance.

Work can be calculated by multiplying the magnitude of the force by the distance.When we consider only the energy contained within an object, we can conclude that energy is constantly moved from one location to another in the form of work. It's worth recalling that elementary school textbooks often define energy as the ability to do work.

Entropy

Theoretically, there exists a limit to the amount of work achievable in any process. That is, not all the energy in a body is available to do work. This maximum (or minimum) can only be obtained when the process follows a reversible path. To put it simply, a process is considered reversible if it can be returned to its initial state without a net addition of work or heat. However, almost every real-world process operates on an irreversible path. As a result, we don't attain the theoretical maximum (or minimum) of work in practical processes.

This leads us to another intriguing question: "What happens to the unobtained work?" For instance, if we determine that the maximum achievable work for a particular process is 10 joules (on a reversible path), but we only obtain 6 joules (because we're doing it on an irreversible path), what happens to the remaining 4 joules? It's important to remember that energy cannot be created or destroyed. Entropy is the property that enables us to quantify this 'lost work'. Entropy represents the portion of a system's energy that is unavailable to do work.

Formula for finding change in entropy. S is Entropy, Q is heat and T is Temperature.

Formula for finding change in entropy. S is Entropy, Q is heat and T is Temperature.The Second Law of Thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics states that in irreversible physical processes, the total entropy of the system and its surroundings always increases. This means that the final entropy must be greater than the initial entropy.

An example of such an irreversible process is when a hot object is placed in contact with a cold object, and they eventually reach the same temperature. If we later separate these objects, they don't naturally go back to their initial, different temperatures.

We can make the following deductions from the second law of Thermodynamics.

- In a reversible process, no work is lost, and the total entropy of the universe remains the same.

- Reversible processes are the most efficient processes possible, and they produce the maximum amount of work or require the minimum amount of work for a given initial and final state.

- The entropy of the universe can never decrease; it can only stay the same or increase. This means that some work is always lost in real-world processes, because real-world processes are never perfectly reversible.

Spontaneous Processes

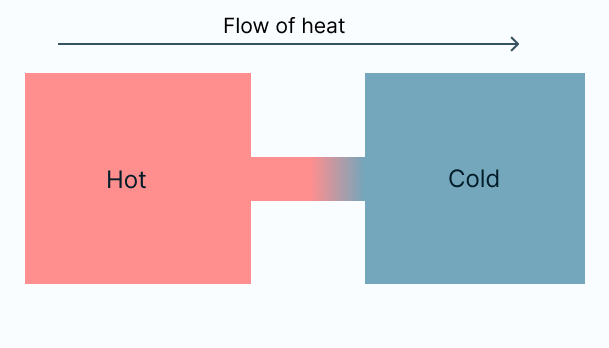

When a hot substance transfers heat to its relatively colder surroundings, it practically cools down. This phenomenon is a common occurrence in our daily lives, but what drives it to happen in this specific direction (from hot to cold) and not the other way round? Additionally, we notice that this cooling process occurs naturally, meaning it happens on its own without any energy input.

In thermodynamics, any process that occurs naturally in this manner is referred to as a spontaneous process. As a general rule of thumb, the change in entropy for any spontaneous process must be greater than zero (i.e positive). Mathematically, Sf - Si > 0, where Sf and Si are final and initial entropy respectively.

A ball positioned at the hill's summit can naturally roll downhill (spontaneous). Conversely, when the same ball is situated at the hill's base, it cannot autonomously roll upward (non-spontaneous).

A ball positioned at the hill's summit can naturally roll downhill (spontaneous). Conversely, when the same ball is situated at the hill's base, it cannot autonomously roll upward (non-spontaneous). In the following section, the connection between entropy and spontaneous processes provides us with an answer to our initial problem!

Heat Transfer

The natural flow of heat from a hot object to a colder one is a spontaneous process, and it contributes to the overall increase in the universe's entropy. This explains why our hot foods eventually cool down, as this transition from hot to cold leads to a positive change in entropy. If, on the other hand, heat were to flow from cold to hot, it would result in a negative change in entropy, violating the second law of thermodynamics. A detailed mathematical proof is available for further exploration..

Regarding the problem introduced at the beginning of the process, we can assert without a doubt that this situation does not contradict the first law of thermodynamics because energy remains conserved. The heat lost by the cold object equates to the heat gained by the warm object, explaining why the warm object becomes warmer while the cold object becomes colder. Nevertheless, we don't observe this phenomenon in our daily experiences because it doesn't occur spontaneously.

Pitfall

The non-spontaneity of a process doesn't imply impossibility. Rather, it signifies that the process cannot occur independently without the addition or removal of energy. This is where engineers play a crucial role. One of the primary responsibilities of engineers is to devise methods for making non-spontaneous processes happen. Appliances like refrigerators and air conditioners are specifically engineered to make non-spontaneous heat transfer happen.

Conclusion

The second law of thermodynamics is a fundamental law of physics that has many important implications for the physical world. It explains why heat is always transferred from hot substances to cold substances, and it can be used to predict the spontaneity of processes and to design efficient engines and power plants.

Reference

Dahm, D. K, Visco, D. P, 2015, Fundamentals of Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics, Cengage Learning, Stamford. p-131